On Saturday/Sunday, May 12/13, 2018 I finished BRM512 (BRM512富士大回り400km), at 400 km my biggest brevet of the year. After having abandoned the 300 km BRM414 AJ NishiTokyo brevet around Mt Fuji due to atrocious weather conditions on April 14/15, 2018 (see report here), I had been a bit nervous about this one. It does an even bigger loop with more elevation gain (3500 m vs. 3000 m) and in my case, because I’m a slow cyclist, more time spent not sleeping.

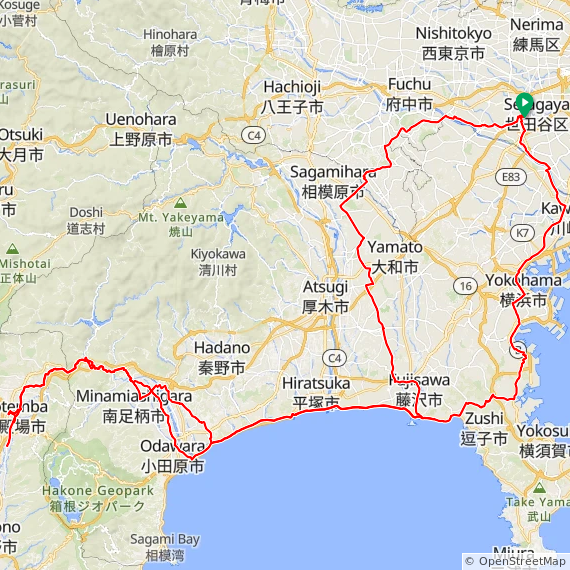

I love the splendid Fuji views and the great variety of scenery that AJ NishiTokyo’s 400 km brevet offers. It covers 4 prefectures (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Yamanashi and Shizuoka). In both years in which I had completed the 400 previously (2015 and 2016), I pre-rode it as a personal ride on my own two weeks before the event, which really helped to prepare myself (2015 and 2016 reports).

On the day of this ride my father, who passed away from cancer about 5 years ago, would have turned 80. As a keen hiker, he would have appreciated the views and the camaraderie of this event. I was thinking of him a lot this day.

Preparing for the ride

The abandoned 300 km in April shook my self-confidence, since it was the first time I had abandoned a brevet on a course that I had successfully completed before, even if it was due to an external influence such as extreme weather. I then decided on a crash course to get into shape for the May ride, still doing only one long ride a week, but picking difficult ones.

Cycling legend Eddie Merckx is often quoted as having advised: “Don’t buy upgrades, ride up grades!” Personally I somewhat doubt he would have said that, given this English play on words would not work well in other languages, that Eddie was from the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium and back in those days he was far more likely to be interviewed by French, Italian, Dutch or German-speaking journalists than English-speaking ones. Nevertheless, as advice it is spot on 🙂

There are a couple of courses that I tend to ride only infrequently (such as once a year or less) because they’re so hard. One of those is the Oume Temple Loop, a mountainous course near Hanno conceived by my friend Deej. Most years I only rode it once, if at all, but then in 2017 I ended up doing it twice just one week apart, each time with a different friend. I really thought that exercise helped me on my subsequent Fuji 300 brevet, which I finished with a personal best time despite insanely hot temperatures.

So for this year I put the Oume Temple Loop back on the menu. One week after the rained-out Fuji 300 I cycled to Oume to pick up six other people and we rode the course. One highlight is the Takayama climb, a big climb of 8 km that gets steeper and steeper and tops out at over 20%.

You will pay for this effort on all subsequent climbs on the ride. The scenery is beautiful though. Many of the rindo (forest roads) are exceptionally quiet. It’s a world apart from Tokyo.

Two days later I announced a repeat of the ride for the next weekend and was rejoined by one of the participants from the first time and three others. Again it was very hard. I don’t know if the memory of the previous ride helped or discouraged, but we did it.

The next weekend I organised a ride up the Kazahari rindo, a forest road in Hinohara with up to 19% that has a reputation for being painfully steep, followed by a visit to the Nippara Limestone Cave.

Altogether I did 5 rides of 178 km or more on the 5 weekends before BRM512. I think especially the Temple Loop rides were excellent training, both physically and mentally.

In the week before the ride I tried to avoid staying up too late and took a nap on some days if I had got too little sleep for some reason. I also watched the weather forecasts for Saturday and Sunday for several locations around Mt Fuji, to make sure there was no chance of rain.

The Monday before the brevet I took my Elephant Bikes NFE to Tim of GS Astuto to install new brake pads and check the rotors as I knew the pads were pretty worn out. It turned out the rear pads were actually worn down to the metal. With fresh resin pads the brakes are fantastic again.

On Friday evening I loaded up the bike to cycle 29 km to Sagamihara, where I had booked a room for the night at Toyoko Inn, so I could get plenty of sleep and would only have to cycle 3 km to the start of the event. Despite having rested the whole week I didn’t feel particularly energetic on the way to the hotel, but it always depends on how you feel the day of the ride. A good night’s sleep can make a lot of difference.

25 hours of adventure

My alarm went off at 05:40 in the morning. I had gone to bed around 22:00 the night before, but woke up twice during the night. I took a quick shower, got dressed and picked up my things to check out. Soon I was on the road. 10 minutes later I arrived at the park for the brevet start. I greeted old friends and picked up my brevet card at the AJ NishiTokyo reception. A lot of the conversations as we were waiting for the briefing were about the last brevet, the washed-out Fuji 300 km. 57 people who had signed up were sensible enough to not even start. I met two of only 8 finishers out of 23 starters. Fortunately the forecast for BRM512 was much more favourable – no rain, a high of about 27 C and a low of about 13 C.

After the briefing and safety check we were off. I think there were about 70 of us. Before we got out into the countryside, we had to stop for a number of traffic lights. At one of them, the lead cyclist wanted to turn left following the course of the brevet in previous years, while the new course went straight. As I pulled up next to her, I pointed out the three areas where the route had changed from the years before. Perhaps she had not studied the new route in detail. I had sat down in front of two computers with two monitors, comparing the old and the final new route side by side about a week before the ride.

I also always make sure to download the route as a GPX file to my GPS so I can follow a breadcrumb trail on its screen, a virtually foolproof way of navigating a course.

Despite the length of the course, even out in the countryside I was often within sight of other cyclists, and sometimes drafting or leading someone. That’s always reassuring, as it tells you that your performance is reasonable enough.

The organisers had replaced one untimed check on the way to Yamanakako with a timed check point near Kawaguchiko, at about 900 m above sea level. Previously PC1 (point de contrôle 1) had been only after the descent from Motusoku, at much lower elevation again, which allows one to make up time lost climbing from sea level to the elevation of the Fuji Five Lakes.

I stopped at one convenience store before entering Doshi road (national route 413) to buy food and some bottled milk tea, then again at the Doshi road station (Michi no Eki Doshi) around km 51. The climb from there to the tunnel felt hard. I was feeling my legs, but I knew the biggest climb would be out of the way and if I could only maintain any time buffer ahead of the required minimum speed that I was left with by then, I could finish the ride by maintaining slightly less than a 15 km/h average, as long as I didn’t get too sleepy.

I saw the first Fuji view around Doshi village and was surprised how clear it looked, because there were some clouds in the sky. Nevertheless, on the other side of the pass, the views got even better.

On the shore of Yamanakako (Lake Yamanaka) I could see the snow-capped peaks of the Japanese Southern Alps, which is actually fairly rare. Half the time you can’t even see Mt Fuji from the lake that lies right in front of it! It was a gorgeous day for views.

From the north side of the lake we followed a minor route, away from national routes 138/139 that we had taken in 2015/2016. The roads were much more quiet. We passed forests and a flower park. Most of it was downhill too. Finally PC1 came up, around km 82. I was 41 minutes ahead of schedule, which was not bad. I bought some food and kept the receipt as proof of the passage.

This 7-11 store was right in front of the entrance to a 2.4 km long tunnel. As I was eating and talking to staff and other cyclists, I saw two cyclists in reflective randonneur vests enter the tunnel without stopping for the PC. Later, as I had almost crossed the tunnel, I saw them come back towards the PC inside the tunnel as they must have realized their mistake.

After the tunnel the route followed the north shores of Kawaguchiko and Saiko, again offering beautiful Fuji views and opportunities for photographs. Then the road climbed to meet up with Rt139, but only followed it for 6.5 km, with the Aokigahara forest on our side.

I was looking forward to the national route 300 turnoff for Motosuko (Lake Motosu). There’s a famous spot facing Mt Fuji where you get the exact same view of it as you see on a 1,000 Japanese yen bank note (well, except for the seasonal amount of snow and the reflection of the mountain on the lake surface depending on how smooth it is with wind, etc). Everybody stopped here to take a picture.

Right after that we entered the tunnel for the Motosu road descent, the biggest and fastest descent on the entire course. On a previous event one of the participants had a bad accident here and had to be airlifted to a hospital, so AJ NishiTokyo staff will always point out to be careful on this descent.

There are some nice views on this descent too and I stopped again for pictures. After the steepest part we turned off for Yamanashi prefectural route 9, which crosses over to an adjacent valley, then another long descent all the way to PC2 near km 133. After the time gained on the fast descent, I was now 1:25 (85 minutes) ahead of the minimum pace.

There were no big climbs on the way to the untimed checkpoint near Minami Alps at km 156, so progress was good. In fact, we even had a nice tailwind. Though this would turn into a headwind on return, the return route also starts with a fair bit of descending that initially more than compensated for the headwind.

I passed a TDK factory in Minami Alps that had beautiful rose bushes facing national route 52.

The checkpoint on top of a loop-shaped ramp provided a nice view of the wide mountain valley at the heart of Yamanashi prefecture, including Mt Fuji. Though it was still almost another 50 km to the half-way point of the ride, it felt like we were already half way there.

There I met my friend Mr O., usually an extremely strong rider, who was resting and looking exhausted. He had not had enough chance to cycle this year to prepare himself. He decided to do the safe thing and retire from the ride.

The return route passed through small towns with a nice descent.

I could still enjoy the Fuji views from the Minami Alps side, which were as clear as from Yamanakako and Kawaguchiko.

Gradually the road became more level and the wind more noticeable, especially after we rejoined Rt52 along the Fujikawa river to the coast. Then we crossed the river near Minobu and followed the Minobu railway line. The road became more hilly and evening approached. There’s a lot of construction going on for the Chūbu-Ōdan Expressway that will connect Chūō Expressway to Shin-Tōmei Expressway when completed.

I don’t really like those hills along the Minobu railway, especially after dark when there are no more views, so I was glad when about half an hour after sunset I reached PC3 in Shibakawa (219 km from the start), 2 hours and 14 minutes (134 minutes) ahead of closing time.

From here it wasn’t far to the coast and I crossed the river, now heading east towards Numazu.

At daytime there would have been more Fuji views, but at night it was just city streets. Every now and then I came across other cyclists who passed me.

I was just keeping a steady pace, every now and then yawning or standing up to relieve my bottom, which was starting to complain about the amount of time spent on the bicycle saddle.

In Numazu the route turned south into Izu. After Shuzenji it became more rural. I was looking forward to the tunnel at the top of the pass and the descent towards Ito. I made it to PC4, 290 km from the start, a little after midnight, now 2 hours and 15 minutes ahead of closing time. I took a 5 minute nap on a chair inside the convenience store. Others were sleeping too.

For the night ride I was wearing long johns under my shorts and also a base layer under my jersey, but no windbreaker which remained unused for the entire ride. It never got cold enough.

It felt great to descend to the east Izu coast line and to finally hear the ocean waves. It was still dark and I could admire the many stars above the ocean, since there was a lot less light pollution than in Tokyo.

Even after the descent there are four significant climbs between Ito and Odawara, the biggest one being for the road high above Manazuru which lasts for about 4 km. I was feeling safe in the knowledge of having made good time so far. I did yawn every now and then, but the nap had helped. My legs felt OK, not particularly strong but not suffering either and my bottom was OK as long as I made frequent efforts to stand instead of sitting throughout.

It was still dark in Odawara but dawn gradually arrived on the ride east to Chigasaki.

I saw newspaper motorbikes deliver morning papers and the odd surfer heading to the beach already. Soon after Rt 30 split off the coastal road I saw the 7-11 sign that announced PC5, the final control (367 km from the start). To get my receipt and to use the toilet, I bought a cup of coffee and a sandwich.

I had only 36 km left and was 2 hours and 4 minutes ahead of closing time. I basically had 4 1/2 hours to get to Machida. Two years ago, I had been one hour ahead of closing time at PC5 and still made it despite a puncture 16 km from the goal that chewed up most of the time buffer.

There were still more Fuji views on the way to Machida. Rain was forecast for the late afternoon and I could see clouds and occasionally feel raindrops, but rain was still a long way off.

Sunday morning traffic and traffic lights slowed me down but looking at the remaining distance and time, I figured I had a chance to make the goal by 08:00, a full two hours before goal closing time at 10:00, so I pushed harder. It was not easy after 24 hours on the road, but I tried anyway. I didn’t know if I would make that time until the very end. It was only when I rolled up in front of the Cherubim Bike Shop, greeted by AJ NishiTokyo staff who confirmed 08:00 as my arrival time, that I knew I had completed the course the full two hours under the limit!

I parked the bike and got out my brevet card and receipts to have them checked. After signing for the result, I opted for the medal (1,000 yen extra). Then I had some coffee and snacks and chatted with staff members and fellow participants about the course and about bikes.

About riding long distances

It’s hard for normal people to comprehend how someone can ride 200, 300 or 400 km in a single ride, but each of these rides builds on previous rides in physically and mentally conditioning you for the next challenge. We dare to do more challenging rides only because we successfully rode other, initially also intimidating rides.

Any road cyclist who has done 50 km rides can do 100 km rides, and anyone who has done 100 km rides will find 200 km rides within reach. As long as you keep the effort sustainable and keep eating and drinking and ride a bike that fits you, you can keep on going for a very long time. At some point, sleep will become the limiting factor, which then becomes a question of average speed vs. control closing times and your tolerance for sleep deprivation.

This 400 km course may actually be becoming my favourite AJ NishiTokyo course, rivaling even the 200 km West Izu (Shiokatsu) course that I also love for its views.

Though it’s longer than the smaller 300 km Fuji ride, I don’t think it’s necessarily any harder. Certainly, in recent years I’ve been able to finish the 400 km with more spare time than in the case of the 300. Perhaps that’s because the effort in the 400 is more concentrated in the first part, when the legs are still fresh, while the 300 saves its biggest climb for halfway into the course. Also, while the 400 has one third more distance than the 300, it only has about one sixth more climbing. This should allow for a higher average speed.

Beyond the 400 km brevet

I won’t be riding the AJ NishiTokyo 600 km brevet to Lake Suwa and back in early June because I’ll be away on a business trip. So there probably won’t be any brevets for me until September or so. Instead I’ll be just riding with friends again, maybe explore some new routes.

Again this year I won’t go for Super Randonneur (SR) status, which involves riding 200, 300, 400 and 600 km distances all in one season. 600 may be beyond reach for me under all but the most favourable conditions, because it’s hard for me to build up enough spare time to sleep enough to keep functioning. Gaining SR status in 2019 is also the qualifying condition for participating in the 1,200 km Paris-Brest-Paris event next August, which I am not currently aiming for.

I very much enjoyed my bicycle tour in Italy with my son Shintaro a year ago, where we only covered about 90 km each day, but had nice meals in little restaurants in the countryside.

If I were to try more cycling in Europe or elsewhere overseas, this is more like what I would like to try, while keeping up randonneuring as a challenge here in Japan.