On my bicycle ride last Saturday I passed a service station near Hachioji in western Tokyo that is being set up as a hydrogen station for fuel cell cars. Japan is in the process of setting up such infrastructure to support a small fleet fuel cell vehicles such as the Toyota Mirai (its name means “future” in Japanese).

For decades, hydrogen has been touted as an alternative fuel for transport once we move beyond fossil fuels. The idea was that it can be made in essentially unlimited amounts from water using electricity from solar, wind or nuclear power (from either fission or fusion reactors). The only tailpipe emission would be water, which goes back into nature.

Unlike electric cars, which have limited range compared to fossil fuel cars, hydrogen cars can be refilled fairly quickly, like conventional cars, giving them a longer operating range. Car manufacturers have experimented with both internal combustion engines (ICE) running on hydrogen and fuel cell stacks that produce electricity to drive a traction motor. Both liquefied and compressed hydrogen has been tested for storage.

Here is a Honda fuel cell car I photographed on Yakushima in 2009:

It’s been a long road for hydrogen cars so far. Hydrogen fuel cells were already providing electricity for spacecrafts in the Apollo missions in the 1960s and 70s. With the launch of production cars and hydrogen fuel stations opening now in Japan, the US and Europe it seems the technology is finally getting ready for prime time. However, the reality is quite different.

Arguably the biggest challenge for hydrogen cars now is not the difficulty of bringing down the cost of fuel cells or improving their longevity or getting refueling infrastructure set up, but the spread of hybrid and electric cars. Thanks to laptops and mobile devices there has been a huge market for new battery technology, which attracted investment into research and development and scaled up manufacturing. Eventually reduced costs allowed this technology to cross over into the automotive industry. The battery packs of the Tesla Roadster were assembled from the same industry standard “18650” Li-ion cells that are the building blocks of laptop batteries.

Li-ion batteries have been rapidly falling in price year after year, allowing bigger battery packs to be built that improved range. A car like the Nissan Leaf that is rated for a range of 135 to 172 km (depending on the model) would cover the daily distances of most people on most days without recharging during daytime. Not only are prices falling and range is increasing, the cars can also harness the existing electricity grid for infrastructure. A charging station is a fraction of the price of a hydrogen filling station.

Here in Japan I find many charging stations in convenience store parking lots, at restaurants, in malls and at car dealerships – just about anywhere but at gasoline stations, which is where the few hydrogen stations are being installed.

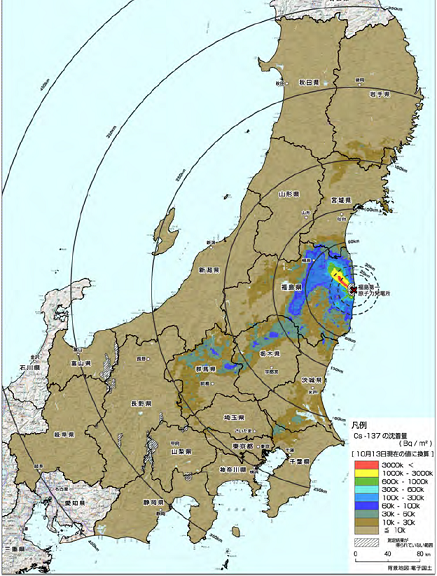

After the tsunami and nuclear meltdown hit Japan in March 2011, some people here viewed electric cars and their claimed ecological benefits with suspicion: The Nissan Leaf may not have a tail pipe, but didn’t its electricity come from nuclear power stations? This criticism is not entirely justified, because electricity can be produced in many different ways, including wind, sun and geothermal. Car batteries of parked cars are actually quite a good match for the somewhat intermittent output of wind and solar, because they could act as a buffer to absorb excess generating capacity while feeding power back into the grid when demand peaks. If cars were charged mostly when load is low (for example, at night) then no new power stations or transmission lines would have to be built to accommodate them within the existing distribution network.

The dark secret of hydrogen is that, if produced from water and electricity through electrolysis, it is actually a very inefficient energy carrier. To produce the hydrogen needed to power a fuel cell car for 100 km consumes about three times as much electricity as it takes to charge the batteries of an electric car to cover the same distance. That’s mostly because there are far greater energy losses in both electrolysis and in fuel cells than there are in charging and discharging a battery. A fuel cell car actually has all of the above losses, because even fuel cells still costing about $100,000 are not powerful enough to handle peak loads, therefore a battery is still required. Think of a hydrogen fuel cell car as a regular electric car with an added fuel cell stack to recharge the battery while the car is running. This means a fuel cell car suffers the relative small charge/discharge losses of a battery-electric car on top of the much bigger losses in electrolysis and fuel cells that only a hydrogen car has.

What this 3x difference in energy efficiency means is that if we were to replace fossil-fueled cars with hydrogen-fueled cars running on renewable energy, we would have to install three times more solar panels and build three times as many wind turbines as it would take to charge the same number of electric cars. Who would pay for that and why?

Even if the power source was nuclear, we would be producing three times as much nuclear waste to refill hydrogen cars than to recharge battery-electric cars — waste that will be around for thousands of years. That makes no sense at all.

So why are hydrogen fuel cell car still being promoted then? Maybe 20-30 years ago research into hydrogen cars made sense, as insurance in case other alternatives to petroleum didn’t work out, but today the facts are clear: The hydrogen economy is nothing but a boondoggle. It is being pursued for political reasons.

Electrolysis of water is not how industrial hydrogen is being produced. The number one source for it is a process called steam reformation of natural gas (which in Japan is mostly imported as LNG). Steam reformation releases carbon dioxide and contributes to man-made global warming. By opting for hydrogen fuel cell cars over electric cars, we’re helping to keep the oil industry in business. That you find hydrogen on the forecourt of gas stations that are mostly selling gasoline and diesel now is not a coincidence. Hydrogen is not the “fuel of the future”, it’s a fossil fuel in new clothes.

Due to the inefficiency of the hydrogen production it would actually make more sense from both a cost and environmental point of view to burn the natural gas in highly efficient combined cycle power stations (gas turbines coupled with a steam turbine) feeding electricity into the grid to charge electric cars instead of producing hydrogen for fuel cell cars from natural gas.

Even if electrolysis is terribly inefficient, by maximizing demand for electricity it can provide a political fig leaf for restarting and expanding nuclear power in Japan. Both the “nuclear fuel cycle” involving Fast Breeder Reactors and the promise of nuclear fusion that is always another 30-50 years away were sold partly as a power source for a future “hydrogen economy”.

While I’m sorry that my tax money is being used to subsidize hydrogen cars, I don’t think hydrogen as a transport fuel will ever take off in the market. Electric cars came up from behind and overtook fuel cell cars. The price of batteries keeps falling rapidly year after year, driven by massive investment in research and development by three independent powerful industries: IT/mobile, automotive and the power companies.

The hydrogen dream won’t die overnight. I expect the fuel cell car project will drag on through inertia, perhaps until battery electric cars will outnumber fossil fueled cars in Japan and only then will finally be cancelled.