TerraPower, a company funded by billionaire Bill Gates, has teamed up with several partners to build a demonstration nuclear power station in Wyoming by the end of the decade. Several sites are under consideration. The plan is to re-use the grid connection of a former thermal coal power plant, of which Wyoming has many.

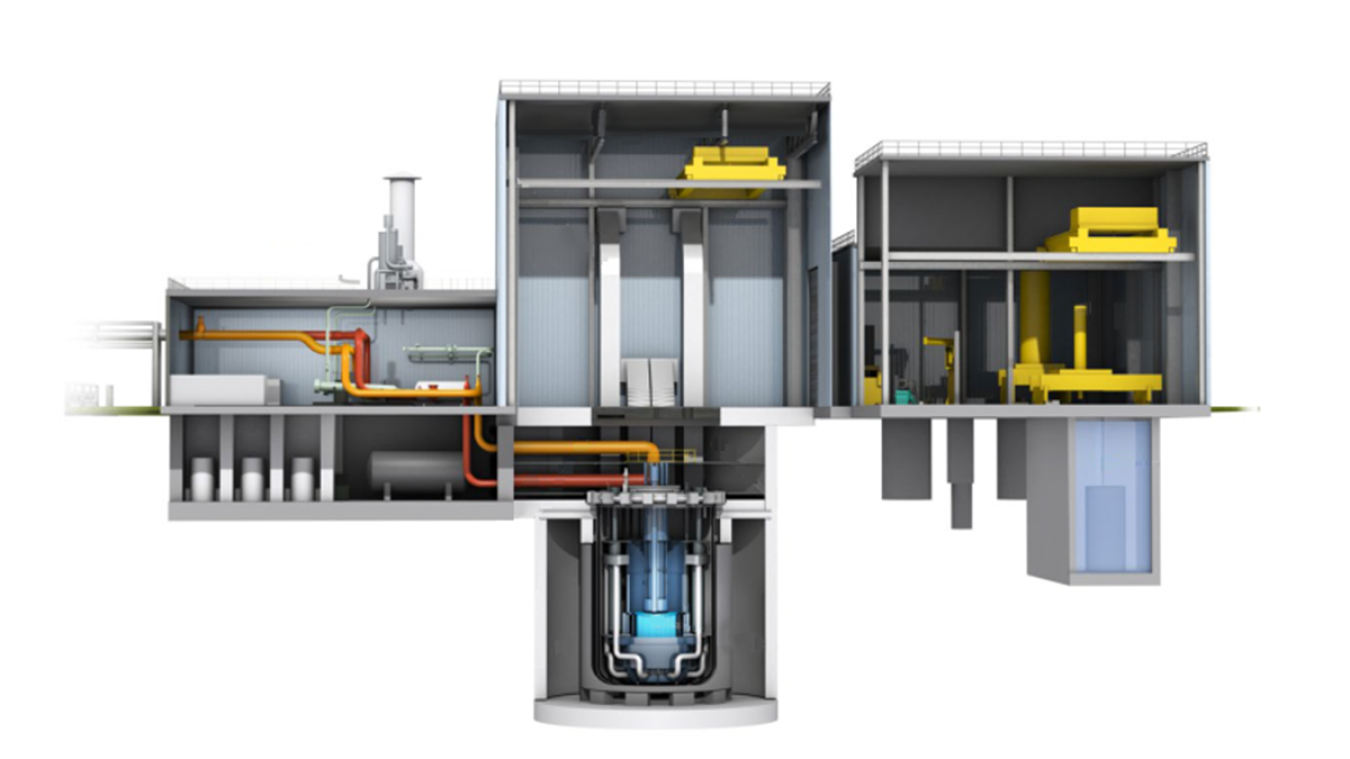

The Natrium reactor developed by TerraPower in cooperation with GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy is quite a departure from the design of the light water reactors (LWRs) that produce the bulk of nuclear power worldwide today. For one, its output is highly variable because it incorporates gigawatthour (GWh) energy storage using tanks of molten salt. The design is quite innovative, which creates both upsides and challenges.

After reviewing the company’s website and watching a webinar, I am quite impressed but also concerned. The reactor will still run on uranium and will produce radioactive fission products that will need to be contained and stored safely for thousands of years. This is still a largely unsolved problem. Countries that have been generating power from nuclear fuels are today sitting on thousands of tons of waste kept in intermediate storage, still without a proven long term storage solution. Eight decades since the start of the “atomic age” with the Manhattan Project that gave us nuclear reactors and atomic bombs we are only now seeing the first permanent storage site being used in Finland. Some consider this the Achilles heel of the nuclear industry. Proponents of nuclear power will argue that, given we already have existing waste, this is a problem we will need to address anyway and that the volume of highly active nuclear waste will remain relatively compact. Nevertheless, there is a lot that can go wrong there, especially if the volume keeps increasing.

What most excited me about the reactor concept was its incorporation of the heat store using molten salt tanks, which it borrowed from concentrated solar power (CSP). Everything from the molten salt tank to the grid connection is basically the same as in this type of solar power plant. The major difference is that the heat source is not solar power focused onto a tower by thousands of mirrors but an underground nuclear reactor. This means the designers could use existing technology developed to maturity over the last 2-3 decades for use in solar projects in Nevada, Australia, Morocco and other locations.

This part of the plant is conventional technology that will not be subject to the same regulatory oversight as the nuclear portion, making it easier and cheaper to build. At the same time, the nuclear portion of the plant is much smaller and simpler, requiring a lot less concrete and steel than in a LWR per MW of output capacity.

By incorporating the heat storage, the electrical output of the power station can be varied considerably – the TerraPower presentation showed a range of about 240 to 500 MWe, with 345 MWe available continually without charging or discharging the heat store. Output that varies by 100 percent roughly covers the demand swing between day and night in many power markets. If combined with solar and wind, the stored heat can be used to smooth out fluctuations in power output from those natural energy sources. Heat from the power station may also have applications for desalination, industrial processes and residential heating.

Conventional nuclear power stations such as PWRs or BWRs can not vary their output very much. They basically can only run at 100 percent load or be switched off. Once shut down, bringing them back up again takes a very long time. That makes them suitable only for base load but not for demand peaks such as in the afternoon or evening. For that they would have to be combined with energy storage such as pumped hydro, opportunities for which are limited by geography. Due to the literally built-in output flexibility of the salt storage system, a zero carbon grid could theoretically incorporate a lot more Natrium output capacity than would be possible with existing LWRs. From an economic point, it means the operators in a competitive electricity market with bidding for supplies can sell more power at lucrative peak prices instead of having to try to find buyers at night when demand and prices are low.

So what’s the catch? The nuclear reactor itself is a sodium-cooled fast reactor (SFR), basically a Fast Breeder Reactor (FBR) without the breeding: Except for the absence of a breeding blanket made of depleted uranium that slowly turns into plutonium, the technology is very similar. Perhaps you remember the Monju reactor in Fukui, Japan that was shut down after a major accident in 1995. The operators attempted to hide the extent of a coolant leak and fire, which led to a 15-year shutdown. After a second accident in 2010 the reactor was eventually decommissioned. In 1966 the prototype Fermi 1 FBR in Monroe, Michigan suffered a partial meltdown. It was permanently shut down in 1972. Several other sodium-cooled fast reactors have been built around the world, such as the French Superphénix, the Prototype Fast Reactor in Dounreay, Scotland and the SNR-300 in Kalkar, Germany. All of the above have since been shut down due to high costs or troubles or, like the one in Kalkar, were never even started up.

While sodium has a high temperature range between melting and boiling point and is a good heat conductor, it also reacts violently with water and oxygen. Naturally, you can not put out a sodium fire with water. Normally the top of the reactor vessel is filled with an inert gas such as argon to prevent sodium fires but it needs to be opened for loading and unloading fuel, during which time the sodium has to remain heated above its melting point. You do not want to start a fire then.

If an LWR overheats, steam bubbles will form that reduce the criticality, interrupting the chain reaction. By contrast, control of the chain reaction in SFRs depends 100 percent on positioning of the control rods.

While the cooling pipes will not have to withstand high steam pressures as in a BWR, they will be subject to thermal stress: The coolant temperature in an SFR is much higher, around 550 deg C (1020 F) which is basically red-hot and hot enough to melt some aluminium alloys (and of course salt, for the heat storage). When SolarReserve decided to build a molten salt CSP solar power station in Nevada, it turned to Rocketdyne to make some of the metal parts, because of their metallurgical expertise in rocket engine nozzles that are also exposed to high temperatures.

There are other viable solutions for base load in a zero carbon grid, such as geothermal power, utility scale battery storage, thermal storage using rock heated electrically with surplus wind and solar or green hydrogen powering fuel cells or gas turbines. Costs for wind, solar and battery storage have been falling rapidly for years. Once renewables are cheap enough, you can partially address issues of intermittent output by overbuilding capacity and simply idling some of it when not needed. Or you can use spare output when supply exceeds demand to produce hydrogen, for making ammonia and for use by the steel industry.

Some of these solutions depend more on geography than the Natrium reactor, which can be installed on any continent and provide power at time of day and in any season. However, it would definitely need to be safe and reliable. Ultimately, this new technology will first have to prove itself.