Japan has been lagging other rich countries on the number of vaccine shots delivered per 100 people. It reportedly comes 37th out of 37 OECD countries. Other countries already started vaccinating in December or early January while Japan didn’t approve of the its first vaccine until February. Vaccinations of doctors and nurses started in initially small numbers in March. The elderly were added starting from April 12, but again numbers were initially very small.

My 81-year old mother in Germany got her second shot before the end of March. My 86-year old mother-in-law in Japan was not even able to make an application before yesterday (May 14) and is now waiting for the vaccination date to come. Tokyo is currently in its third state of emergency, struggling with its fourth wave of infections.

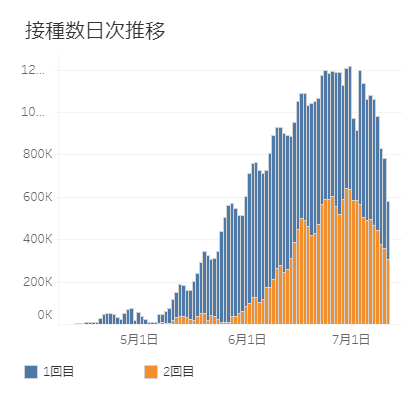

For the last 7 days with published numbers for vaccinations of healthcare workers and elderly residents (2021-05-05 to 2021-05-13) the daily average is about 193,000 doses per day. At that rate it would take 3 1/2 years to finish vaccinating the entire population.

Even other rich countries in the Pacific region that (unlike Japan) currently have few new Covid cases have vaccinated far more of their population. For example, with only 5 Covid-19 deaths in the past 12 months New Zealand has been virtually Covid-free, yet it has vaccinated proportionally twice as much of its population than has Japan. The same is true for Australia and South Korea, which both have proportionally fewer cases but more vaccinations.

Like other countries, Japan has struggled to secure sufficient vaccine supplies, but that is not the whole picture. Starting from April, far more vaccine doses have been arriving than were being used, leaving 24 of 28 million doses imported by the end of April still unused in early May.

According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) the expected vaccine supply in May and June should allow for bringing in enough Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for the entire 36 million residents aged 65 and above by the week starting 2021-06-28, which should allow giving everyone the first shot in early July, knowing there will be enough vaccine for the second shot three weeks later, thereby finishing to vaccinate the 65+ population by the end of July.

As an aside, Japan rigidly adheres to the 3 week interval set by the manufacturer, unlike the UK and Germany which had lengthened the interval between shots to maximize early partial immunity by giving as many people as possible a first shot: The protection given by the first shot is considerably stronger than half the final protection from both shots, so fewer people will become ill or die in a population of 10 million if 1 million are half-vaccinated than if 500,000 are fully vaccinated but the rest non-vaccinated.

Shipments arrive in boxes of 195 vials. Starting from the week of 2021-05-10, all boxes will be paired with low dead space syringes needed for 6 doses per vial = 1,170 shots per box. Previously only 5 doses could be extracted with the available syringes (975 shots per box).

2021-05-10 + 2021-05-17: 16,000 boxes = 18,720,000 doses total

2021-05-24 + 2021-05-31: 13,000 boxes or more = 15,210,000 doses or more

2021-06-07 + 2021-06-14: 13,435 boxes or more = 15,718,950 doses or more

2021-06-21 + 2021-06-28: 13,434 boxes or more = 15,717,780 doses or more

The “or more” in the numbers above refers to extra supplies that may be released from the central government’s stockpile whose size they don’t normally talk about.

Combined with the much smaller numbers in April that’s a total of 62,710 boxes, enough for two doses each for 35,490,000 residents aged 65 or above.

With supplies secured, the big question will be how fast the vaccine can actually be distributed. With the national government only taking care of import and distribution of vaccines, the actual vaccinations are left to local governments and are happening in a patchwork of different approaches. For example, in Setagaya where I live, the city website lists quite a few public vaccination sites to be set up at event halls, gymnasims, etc. in the next couple of weeks and months. There’s a website to make online reservations, once your mailed coupon arrives. This is similar to the approach in Germany. In my mother-in-law’s city in Saitama prefecture however, the city lists hospitals and small clinics, none of which can be reserved online yet (reservations are by telephone only) and many of them will currently only accept people already on their patient register. That approach is not very encouraging for cranking up the volume.

The central government-run vaccination sites to be set up in Tokyo and Osaka that are supposed to handle 10,000 and 5,000 vaccinations per day respectively will not be a game changer unless there will be many more such sites operating everywhere for the rest of the year. 10,000 shots a day for 3 months (the planned operating time of the Tokyo/Kanto site) will cover 2 shots for 450,000 people, a mere 5% of the 65+ population of Tokyo+3 (Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba) of 9 million and then there will be the much larger under-65 population still to take care of.

The next group in line will be the under-65 with pre-existing conditions, then everybody else (probably in decreasing age order). Japan will need many more mass vaccination sites, it will need to recruit and train staff (both people with a medical background and volunteers) and maybe also change some regulations to widen the circle of people qualified to give injections. Otherwise the vaccination process could drag on far into next year. Another winter with another wave of infections and an unpredictable cost in lives and economic pain would be disastrous.

See also: